Review: Atlas Shrugged Part I

Well received by audiences, despite low budget

Since its 1957 publication, Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged has been one of America’s most controversial and influential novels. After numerous failed efforts, financier John Aglialoro and director Paul Johansson have finally brought a film adaptation of the novel to fruition. On Friday, April 15th, “Atlas Shrugged Part 1” opened in select cities across America.

The movie follows Dagny Taggart’s (Taylor Schilling) struggle to save her family’s decaying company, Taggart Transcontinental, from crippling government intervention and her brother’s (Matthew Marsden) incompetence and corruption. To save the company and replace its deteriorating rails, Dagny invests in Rearden Metal, a revolutionary new alloy created by Hank Rearden (Grant Bowler).

Dagny finds a kindred spirit in Reardon, a fellow industrialist Randian hero, and a friendship soon develops from their professional relationship.

Meanwhile, leading industrialists are disappearing and the American and world economies are spiraling downward at a terrifying rate. As Dagny tries to save her company, she questions the world’s economic decay, but her frustrated pleas fall on those resolved to their fate. They dismissively retort, “Who is John Galt?”

Meanwhile, leading industrialists are disappearing and the American and world economies are spiraling downward at a terrifying rate. As Dagny tries to save her company, she questions the world’s economic decay, but her frustrated pleas fall on those resolved to their fate. They dismissively retort, “Who is John Galt?”

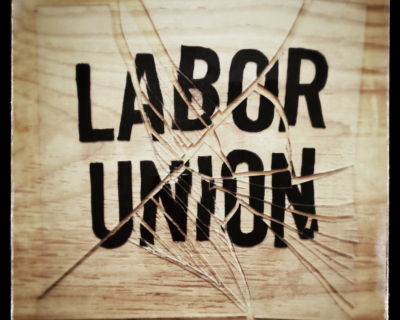

Dagny battles public opinion and academic criticism but eventually they become too much and is she is forced start a new company to save Taggart Transcontinental. She calls it the “John Galt Line,” as a defiant response to the echoed question. This battle – an ambitious individualist against parasitic and stifling collectivists – captures a primary conflict of Rand’s philosophy, Objectivism.

As an epic novel that took twelve years to complete with an incredibly intricate plot that unfolding over more than a thousand pages, Atlas Shrugged deserves treatment similar to that of Lord of the Rings. Instead, it received less than a year’s preparation and a $10 million budget necessitated a shorter running time.

Ayn Rand believed that art, specifically writing, should include only the essential, so her writing is dense and careful. Because of this, perfectly condensing Atlas Shrugged into a movie, even a three part one, is a near impossible feat. The filmmakers did a relatively good job of deciding how to pack the story into less than two hours of film, but the story’s still suffered from the reduction.

Consequently, it has received heavy criticism from reviewers. However, considering these constraints, its quality is neither surprising nor particularly disappointing. In fact, “Atlas Shrugged: Part 1” was highly enjoyable, and I was satisfied with the movie’s fidelity to the book.

Had I not previously read the book, though, it would have been easy to get lost in the scene changes. The movie moves faster than it should, pulling the viewer from scene to scene. Sometimes scenes change without sufficient explanation, alienating the viewers. At other times, the writers oversimplify, as in their treatment of the industrialists’ disappearances.

The immediate explanation of missing persons came across as cheesy and removed much the mystery and subtlety from Ayn Rand’s novel. By the end of the film, I had learned more about the disappearances and their connections compared to when I finished reading part one.

There has also been considerable criticism of the characters’ flat affect, and some of this is warranted. Dagny and Rearden do have a relatively flat affect. This is purposeful; their emotions are not supposed to be plastered across their faces or conveyed through outbursts of inflection. But they are supposed to be conveyed. The book achieves this through dialogue, actions, thoughts, and memories. Unfortunately, thoughts and memories are absent from the movie.

For example, the portrayal of Rearden’s internal struggle is incomplete, as is a relationship between Dagny and Fansisco, the worlds leading and copper baron, mysteriously turned playboy. In the novel the two shared an intensely passionate romance during their youth. Yet the filmmakers relied purely on present action and dialogue to convey the characters emotions. Again, this is understandable given the time constraints, but it resulted in characters that were much less multifaceted and emotionally invested than those in the novel.

However, those who criticize the characters as they appear in the book rather than their on-screen portrayals for their lack of emotion and realism are missing the point. Ayn Rand was a Romanticist. She believed that art should portray an ideal. She specifically rejected the naturalist movement, which sought to make art as accurate a reflection of daily life as possible. Rather, she modeled her heroes, not on the humans she encountered, but on what she thought man could and should be.

The heroes of the Atlas Shrugged are rational, calculated, focused, controlled, and purposeful, but they are also intensely passionate.

The heroes of the Atlas Shrugged are rational, calculated, focused, controlled, and purposeful, but they are also intensely passionate.

Dagny Taggart is passionate about Taggart Transcontinental and providing the best possible train transportation–about excellence, and about competency. This passion is made clear in her actions and her rare but intense displays of emotions, especially in the last scene. She has emotions, but she is not a slave to them, and she avoids displaying them prominently when it would be counter-productive to do so.

The same is true for Hank Rearden, Ellis Wyatt and Francisco D’Anconia. In fact, all of Rand’s heroes have strong emotions. Those who miss this tend to do so either because they believe that business is not a legitimate object of passion, or that emotional control somehow reduces or invalidates emotions.

Many other aspects of the movie were successful. There were few clues that the budget was less than most mainstream films, which was impressive considering the film’s style and content. It did not tackle a subject matter typical of B movies – rather, a story that stretched across America from New York skyscrapers, to Wisconsin factories, Colorado oil fields, and a diner in Wyoming.

The cast was also well chosen. No character felt inappropriate or out of place. Tremendous attention given to detail and maintaining fidelity to the novel. And the changes were made from the original story, although perhaps regrettable, were done with purpose, not haphazardly.

The adaptation to modern times is particularly graceful and intelligent. The movie integrates the original story perfectly into a modern context, and highlights how relevant it is today.

Perhaps most importantly, the movie stays true to the philosophy of the book.

Five friends joined me to view the film, one of whom had read the book. All could tell that there were flaws in the cinematography, but their response, overall, was positive. So was the opinion of our fellow theater goers. The end credits were met with an ovation, a phenomena that has been occurring in many of the films screenings.

Despite heavy criticism in some circles, the message and the movie are being well received, and are incredibly timely. This is apparent in both the buzz it has generated in the media and the money it is generating at the box office. The movie, which played in 299 theaters on opening day, is slated to break 1000 theaters by the end of the month. The $1.7 million earnings, an average of $5,590 per theaters, made it one of the nation’s most popular three films this week.

This reception matches the novel’s, which upon publication was flamed by critics but almost immediately became a best seller. Already, the filmmakers appear to have plenty of audience anticipation to work with. And If this trend continues they will have greater resources at their disposal when making the next two installments.

“Atlas Shrugged: Part I” is playing in New Orleans this week at The Theatres at Canal Place.

Charlotte McCray is a research assistant with the Pelican Institute for Public Policy. McCray studies philosophy and economics at Loyola University in New Orleans, and you can follow her on Twitter.

.