Legislators Attack Jindal’s Plan to Privatize Prisons

Specialists recommend altering truth-in-sentencing policies to reduce costs

NEW ORLEANS, La. – Gov. Jindal’s plan to sell three state prisons to private prison operators has generated criticism from prominent legislators and state officials. Rep. Patrick Williams (D-Shreveport), Rep. Page Cortez (R-Lafayette), among others, say private prisons would, in the long-run, increase state costs.

These lawmakers also disagree with the idea of using a one-time sale of state facilities to pay for operating expenses such as Medicaid.

“It seems to me like we’re selling prisons to cover a hole this year,” says Rep. Page Cortez (R-Lafayette), “but we haven’t addressed covering the hole next year.”

Paul Rainwater, Gov. Jindal’s top budget advisor, counters that the one-time money would help private health providers navigate a tough financial year. He also believes privately run facilities would cost less on an ongoing basis.

Paul Rainwater, Gov. Jindal’s top budget advisor, counters that the one-time money would help private health providers navigate a tough financial year. He also believes privately run facilities would cost less on an ongoing basis.

19 states, including Mississippi, have implemented private prisons in order to reduce correctional costs. However, a recent American Civil Liberties Union study found that from 1994 to 2007 the Mississippi Department of Corrections, which began outsourcing to private prison companies in 1995, increased its budget by 155 percent. Mississippi also has the second highest incarceration rate in the country, behind only the world leader in incarceration, Louisiana.

Forest Thigpen, President of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, disputes ACLU’s conclusion, stating that private prisons do not account for the increased corrections spending. Rather, “it is due to ‘truth-in-sentencing’ laws that were enacted in the 1990s to require convicts to serve most of their sentences.”

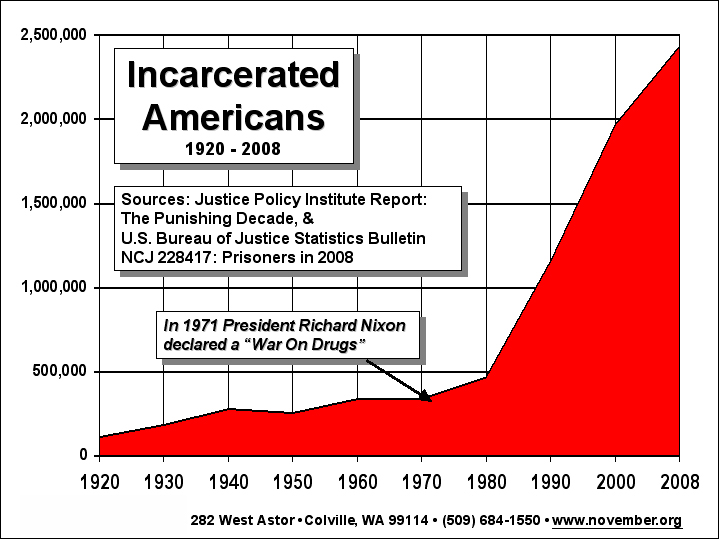

Adam Gelb, director of the Public Safety Performance Project at the Pew Center on the States, agrees with Mr. Thigpen’s assessment. Gelb, who has been working with Governor Jindal to reduce Louisiana’s prison population, notes in his 2008 Pew study, “One in One Hundred: Behind Bars in America 2008,” that the growth of the United States prison population is not driven primarily by increases in crime or population.

“It flows principally from a wave of policy choices that are sending more lawbreakers to prison, and, through popular ‘three strikes’ measures and other sentencing enhancements, keeping them there longer.”

In his recent testimony before Congress, Mr. Gelb stated that although the U.S. prison population has tripled since the 1980s, crime is still well above the levels we had through the 1960s, violent crime is still intolerably high, and recidivism rates have not decreased.

“Over the past 10 years, seven states have reduced their crime rates and incarceration rates, firmly debunking the notion that if imprisonment goes down, crime will go up.”

Robert Ross is a researcher and social media strategist with the Pelican Institute for Public Policy. He can be contacted at rross@pelicanpolicy.org, and you can follow him on twitter.