Guest Commentary: Education – Investing Smarter

An exclusive focus on inputs such as teacher headcount ignores vital dynamics such as the parent-student relationship

I’ve spent the last few months in Louisiana, a state that received an “F” in Education Week’s 2011 K-12 Achievement indicator scoring. I moved here to take the COO position of an economic development organization representing just under a million people and 1,500 businesses. In my many discussions with community and business leaders concerning the future, economic competitiveness, crime, poverty, and wages, each has cited, without fail, the critical need for a strong public educational system.

The United States recently fell to an “average” rating in international education rankings by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. U.S. scores in reading, science, and mathematics landed us in 14th, 17th, and a “below average” 25th place (out of 34) in each subject area respectively. Speaking about the results, U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan told the Associated Press, “this is an absolute wake-up call for America, […] We have to get much more serious about investing in education.” Before we start “investing,” though, let’s figure out exactly what that means.

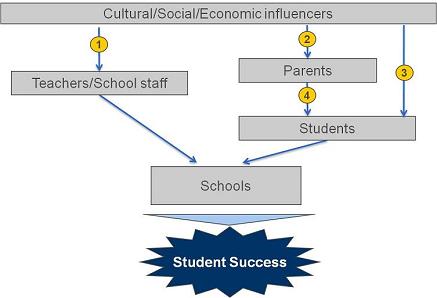

In spite of widespread acknowledgement of education’s importance for our future, we’re struggling to make significant improvements. Why? We have focused too much on the direct inputs to schools – students and teachers/staff – and not enough on other dynamics that are related to those inputs. This is not to say that these areas and their associated metrics are not important – they are very important. However, an exclusive focus on figures such as funds per student, or teacher headcount, ignores other vital dynamics ranging from socioeconomic factors to the parent-student relationship. The chart below highlights four.

Understanding this system makes it clear that a strategy of “investing” in teachers/staff and students is incomplete. This writing, the first of two parts, is intended to help break down and identify the problems in a new, straightforward light. We need to think critically about all four elements identified above, before we can develop real solutions to our educational crisis.

Element 1: In many cases, cultural, social, and economic influences have preserved teachers and staff in their roles for the wrong reasons. Unions, collective bargaining, and tenure have created a profession where job security is linked to seniority, and too often allow the wrong teachers to coast through paycheck collection despite poor performance, while holding back rewards for great performance. Out of a misplaced sense of loyalty, these unions routinely protect their members from any reforms, instead of protecting their students. Examples can be taken from around the country, including, famously, the public schools in our nation’s capital. The teacher’s union in Washington, D.C. is threatening a class-action lawsuit to undo the dismissal of 241 ineffective teachers. (Former D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee has already been forced out of her position.) We as communities have allowed this to happen. We hold the ideal of teaching in abstract awe without demanding from teachers and staff the values and performance that comprise this ideal. We’ve shied away from any criticism of teachers at the fear of our own disabuse.

Element 2: Our culture needs to, in honest reflection, ask itself whether it fosters and encourages parents to value and be involved in education. Historically, community schools did this well – small communities where parents couldn’t help but run into the principal, or their son’s or daughter’s teacher in the grocery store, church, etc. This model now outmoded, we have outsourced education to the school district with the expectation that no other involvement is needed. Too many communities, faith groups, and families have stopped holding parents accountable – this is critically amiss and the effect becomes amplified in the parent-student relationship. Communities need to become actively involved in education. Faith groups – imbued with centuries of leadership in many forms of education – must lead here too. Those whom we elect to school boards need to promote such involvement in their districts and set aggressive goals for improvement. Parents need to go beyond discussing problems with their children and friends, to discovering and implementing solutions. Parents also have a role to play as the foremost advocates for their children. Who better to hold the school board accountable? This is not to say that communities, churches, school boards, or parents will take the place of the teacher. It is to say that they are part of the process – and that their involvement is important and valuable.

Element 3: In some places it’s finally cool to be smart – but usually not among the students and communities where this is most needed. Silicon Valley’s Mercury News reports that Sandra Romero and Bibiana Vega of San Jose were called “whitewashed” and told they were “losing their culture” because of their high GPA’s. Another story was retold to me of a Louisiana boy in an impoverished neighborhood who was bullied after school for bringing books home. This issue is subsiding in some areas. Programs like the FIRST Robotics Competition and movies like “The Social Network” excite young people about what’s possible when you’re young and smart. But these programs are too few, and Hollywood won’t solve this. Nationally we need to renew our campaign, especially in low-income communities, to demonstrate the value, importance, prestige, and opportunities associated with education. Parents also have an important role to play in defining students’ cultural expectations.

Element 4: Parents need to be actively engaged in encouraging the educational success of their children, every day. The literature from developing economies shows that one of the most important factors in the next generation of women’s economic well-being is the literacy rate of their mothers. The same rules apply here in America. Parents who read with their children at an early age, and remain engaged with their child’s education throughout school, will have higher performing students. Going back to our outsourced education attitude mentioned earlier, this is more than just showing up to a parent-teacher meeting, or reading the school newsletter. This is checking up on homework, helping on homework, and limiting TV and video games. More than just checking a box – this is real engagement. This is also difficult, especially in single parent households, and households where work schedules may limit the amount of time parents can spend with their children. In these cases, reliance on the community becomes even more important.

The interplay between all of these elements is obvious. With the problem more structured and illuminated, my next essay will look at concrete examples of how people are addressing these problems comprehensively – and effectively – all around the U.S.

Solving any singular element isn’t going to fix the entire problem, just as continued focus or “investing” in teachers, staff, or students does not provide a complete solution. In the pockets of fantastic reform and success that have developed around the country, you will see that multiple issues have been addressed in parallel. It’s time for this approach to become the model: for reform to occur along all avenues of influence and input, and for all us to recognize our part to play, to commit to reform, and to get involved.

This article first appeared on upsidepolitics.com.

This article first appeared on upsidepolitics.com.

Giles Whiting is the executive vice president and chief operating officer of the Baton Rouge Area Chamber.