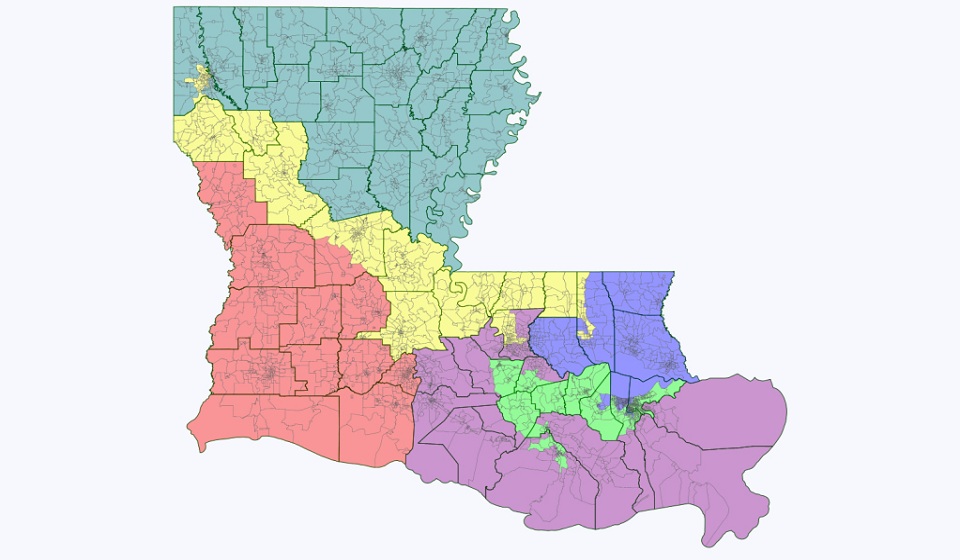

Guest Commentary: Louisiana Redistricting Plan Should Clear, Unless Politics Interfere

LSU-Shreveport professor explains blurred constraints on Louisiana’s redistricting

As Louisiana embarks on redistricting, the lack of familiarity with the decennial process and the law involved can create much confusion. Hence, some words of clarity can help to explain the likelihood the chambers’ current plans coming to fruition.

First, unlike the strict requirement of population equality for Congressional districts (that they have equiproportional populations “as nearly as is practicable,”stemming from Wesberry v. Sanders), the standard for state and local districts has been for “substantially equal” legislative representation” (from Reynolds v. Sims). In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court has never set down a hard-and-fast rule on acceptable population deviation. It has, however, created a locus of around 10 percent, with extenuating circumstances allowing for even greater deviations to be upheld and lesser ones overturned.

While Louisiana lawmakers set an internal target of five percent, legally they could go as high as 10 percent. They could go higher still to achieve compactness, respect municipal boundaries, preserve cores of prior districts, avoid contests between incumbent representatives, and provide representation to political subdivisions. It’s likely the five percent standard will be enforced during, but there is no legal reason that it must be.

Second, suggestions that some kind of derivation of voting strength be used instead of population count have no history as use for drawing districts and no legal pedigree. The question concerns drawing boundaries to create majority-minority districts where social science research suggests some ethnic groups are less likely to register to vote and to vote than others. Age demographics are another concern, since some populations may be younger and also less inclined to participate in elections.

Therefore, for example, in a district of 60 percent self-identified blacks, they may only comprise 55 percent of the electorate that turns out to vote. Drawing districts like this could be interpreted as an attempt to dilute black voting, forbidden by the Voting Rights Act. This interpretation, however, runs counter to the language of the Act and subsequent court decisions that promulgate that there is an affirmative right to the franchise, but not one to vote.

Thus, there is no requirement for the state to draw districts to maximize ethnic voter turnout (if such a applicable standard could even exist to determine that, echoing Davis v. Bandemer). Rather that the state draw districts with ethnic majorities, where legally practicable, whose proportion of all districts echo roughly the state’s proportion of ethnic populations.

Third, the Voting Rights Act applies only to select states and other jurisdictions, but it applies to Louisiana in its entirety. The point is to avoid an obvious dilution of ethnic voter strength, unless there are present compelling reasons, as with deviations from equiproportionality. That means, if Louisiana has a self-identified black population of 32.8 percent, you don’t have to have (rounded) 105 x .328 = 34 House seats or (rounded) 39 x .328 = 13 Senate seats with black majorities.

As long as no intent appears to discriminate on the basis of race, it doesn’t matter how many seats there are. That includes the drawing of boundaries intentionally to maximize creation of majority-minority districts as the Supreme Court elucidated in Louisiana’s own U.S. v. Hays.

The argument that a closer number of self-identified-black majority districts relative to their proportion of the state’s population might lead to fewer legal problems is not incorrect. But that does not mean any plan with more majority-minority districts than any other, if both are below the proportional number, automatically is better or to be preferred. To draw on that basis in fact runs the risk of the unconstitutional practice of drawing predominantly on the basis of race.

While Voting Rights Act considerations may seem cryptic, they are crucial to the process because they are checked by the U.S. Department of Justice or courts. The Section 5 procedure known as “preclearance” requires states under the VRA to submit changes to existing electoral administration before they may be ratified into law or regulation. Whatever Louisiana comes up with for its Legislature must get this clearance (within 60 days after submission for the Justice Department).

However, Section 2 of the VRA allows subsequent legal challenges. In other words, successful preclearance does not immunize plans from legal action. Sometime in June when the state should receive notification of successful preclearance, those dissatisfied with the plan may still try to block implementation of the plan – if not for this election cycle, then future ones.

At present, the plans for both chambers emanating from them appear within judicial and VRA standards. The House plan would increase to 29 minority-majority districts from 27 and the Senate would one would go from 10 to 11. Of some concern may be that the Justice Department under Pres. Barack Obama already has demonstrated an affinity to politicize the voting administration process.

While a Section 2 suit would allow fall elections to proceed, failure to obtain Section 5 preclearance would cause chaos. Still, given that Justice rarely has objected to preclearance for a couple of decades now, the plans proposed by chamber leaders look worthy to pursue.

Jeffrey Sadow is an associate professor of political science at Louisiana State University, Shreveport. The original version of this article first appeared on Sadow’s blog, “Between the Lines.”